John Allan Masese was born in 1944 amongst the rich shades of green and yellow that made up the grandiose plantations of Kericho. The aroma of long-lost tales traveled in and out of the valleys, burnt and hidden under layers of distortion. Masese's father worked within the endless fields of tea, the boy, little and lithe, often listened with frightful ears to the events unfolding just over the valleys. They would whisper 'The Mau Mau have moved on to... and have captured...'. He listened with fear, imagining and mentally preparing for the possibility of his family's demise.

Even worse was the looming anxiety of the European defense forces wreaking havoc, shooting randomly or raiding the people. They justified this under their so-called 'moral obligation' to restore peace by any means necessary. To regain "their" colony, "their" Kenya. John lived with a constant dread that one day, he too might become a victim of an event similar to the Lari massacre.

As the dew hung heavy on the budding grass, John rose with the sun. Alongside the other shadows in the morning mist, John would go off to school. Off to a dimly lit classroom to read off a blackboard and learn of situations a lifetime away from his own. His classrooms overflowed with both young Black boys and brilliance. Yet, forced into learning only of selective history that frequently excluded them unless when discussing their people's subordination. In the breaks the boys huddled, convening to share the stories they had heard the night before. Fright shrouded with a sort of humor.

'They say so and so is hiding a pistol underneath his hair,' they giggled, laughing at the absurdity whilst internally longing for more information. Apropos of this amusing niter-natter was an officer who used to ride a motorcycle around the province, his hair growing like a healthy tree, round and trimmed. He could well have a pistol hidden within those branches. The officer was taken to the detention center soon after under suspicion of being a Freedom fighter.

As the seasons turned and the jacaranda trees bloomed, turning the wind a vibrant shade of purple, John's primary school was coming to an end. Amongst 30 others in a cramped room, he was handed an exam paper. The Common Entrance exam for the Africans. The whites were allowed to take the KCPE Kenyan Certificate of Primary Education. They didn't have to worry about the next stage in the same way he did. The way the 30 others did. They all knew the chances of making it to the next stage were slim as they spitefully scratched at the paper with a feeling of inferiority devouring their minds. The process of sieving had begun. 15 passed. Only 3 including John were able to go to secondary school.

High school was a different experience. The law now forced European schools to take all races. Of course, treatment was not the same, and much like other aspects of society, privilege was 'a gradient-white, Asian, then Black'. However, change was on the horizon and all Kenyans were beginning to see a future of choices. Choices for them, by them. Looking to the future, there was only one university - The University of East Africa in Dar Es Salaam. Opportunities for higher education were scarce in East Africa. There were constituent colleges spread out across the region like Makerere in Uganda but all in all 'there were very limited institutions for African learning'.

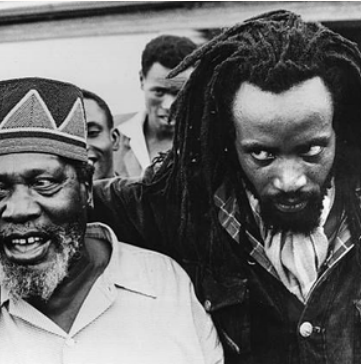

Amid this landscape, on one pivotal day, incoming president Jomo Kenyatta was released. Word spread in a matter of minutes that he would be passing through the Kisiitown Kisumu Highway a somewhat close distance to John's school in Nyaparoro. The air throughout the school fizzled with anticipation. Students daring to request allowance to witness the momentous event were met with a red-faced headmaster. 'No, you can't, that's not a good person to go and see. He doesn't even believe in God!'. To the white Headmaster, this was the genesis of a recession, just as it was a progression to the Black people. Regardless the students rioted and ran to observe the passing car, cheering with a new sense of honor and dignity within their souls.

As a result of their disobedience, they were met with manual labor punishment. The next week they became slaves, their education revoked, and their bodies put to work. Despite everything, Masese was content. The sense of satisfaction gained surpassed consequences. He witnessed a turning point in Kenya's history. Slowly changes began to shape the nation. Prince of Whales School became Kenya High School; hospitals began to accept patients based on need rather than race. 'Land-less' Kenyans moved from the small, overcrowded "native reserves," which had been 'graciously' allotted to them on the White man's thousand-acre estate, under a 999-year lease from the distant British monarchy. Then, in 1963, the rise of internal self-government began to shift the balance of legal and social power, offering Africans better opportunities and making liberties an entitlement instead of a privilege.

Post Kenya's achievement of independence (1962), John attended the newly established Kenyan School of Law. It was founded under the collaborative agitation of the Kenyan government and a group of local lawyers. As John entered the legal field, remises of the struggle for equality remained evident. There was a huge gap in the profession with roughly 99% of lawyers being white and non-African. Simply put, there was much to be done that could not be achieved in a fleeting instant. Despite the achievement of freedom from Britain's grasp, there were more people to be trained and more institutions to be founded.

In a nutshell, independence brought numerous opportunities to local people socially, economically, and politically. The political shift fostered a never-before-seen environment where human rights became accessible to all races. While Kenya's constitution no longer supports discrimination, the ongoing battle in certain parts of the republic persists, with tradition and statute remaining at loggerheads. Masese provides the example of a young widow left with only a daughter to inherit her late husband's land. Dissatisfied with this option she adopted 4 boys; however, they greeted her with foul treatment. The lady decided to give her daughter a piece of the land, leaving the rest to the boys. The community was in uproar, chasing the girl away despite a court order allowing her to own the land. Steeped up in tradition they went against the government itself.

Only by reconciling the past can Kenya fully realize its purpose within progress and unity. As John puts it, "Kenya is the best in the world". But to truly be the best, progress must be relentless, and the courage to evolve must never waver. The fight must continue, and the openness must stay consistent. For John, experiencing independence meant a myriad of opportunities unfolding before him . The struggle has shaped who he is today, allowing him to practice and teach law as a Kenyan citizen . However, it is essential to recognize that implementation of the progressive reforms remains challenging .